The Unsinkable Charles Lightoller

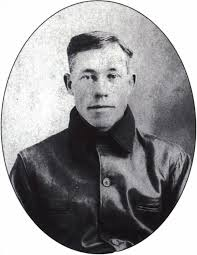

/When Titanic’s Second Officer Charles Lightoller knew the ship was sinking, he wasted no time in asking Captain Smith for orders to fill the lifeboats. He’d seen plenty of trouble at sea before. Working aboard ships since the age of thirteen, he’d already survived one shipwreck, a shipboard fire, and a cyclone, all by the time he’d turned twenty-one.

In his early twenties, “Lights” Lightoller had been working aboard a steamship on the West African coast when he nearly died from malaria. He took a break from his life at sea and went prospecting for gold in the Yukon, became a cowboy in Alberta, Canada, traveled as a hobo by train across Canada, and found a job on a cattle boat back home to England. The call of the sea won out, and he studied to become a ship’s officer. Joining the White Star Line at age twenty-six, he met a passenger on a voyage to Australia. She became his bride on the return trip.

Under the command of Captain Edward Smith who later would captain the Titanic, Lightoller held the Fourth Officer’s position aboard the Majestic for some time. He was then promoted to Third Officer on the Oceanic, Titanic’s sister ship. When preparations were underway for Titanic’s maiden voyage, “Lights” was originally set to be its First Officer. But Captain Smith brought on another officer from the Oceanic as his Chief Officer, shifting all the other officers’ positions. Lightoller was forced to accept the role of Second Officer, while the original man in that position had to drop out.

Charles Lightoller, second from left, with Titanic officers. Captain Smith on far right.

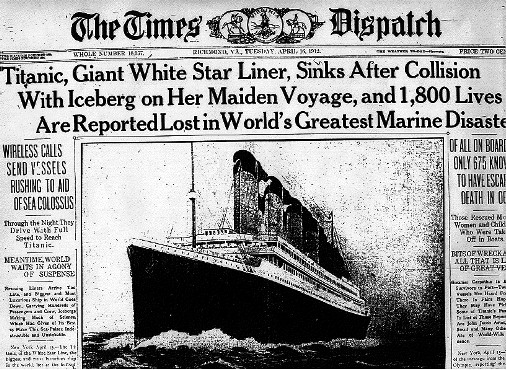

On the night of April 14, 1912, Charles Lightoller noticed the abrupt drop in temperature, even though the winds and waves were calm. During his evening duties, he alerted those in the crow’s nest to watch for small ice. Ships in the area had sent repeated ice warnings during the afternoon, but not all of them reached the bridge, preventing the officers from knowing the full extent of the warnings.

After completing his rounds, Lightoller went to his cabin. As he fell asleep, a grinding sensation awakened him. He ran to the deck in his pajamas to investigate. Within minutes, he was informed that water was rapidly filling the mail room. He returned to his cabin to grab his uniform coat and was soon directing crewmembers in the launch of the boats.

When all lifeboats had been lowered and three of the four collapsible boats had been launched, Charles Lightoller climbed onto the overturned Collapsible B as the Boat Deck went underwater. Hours later, he made sure all passengers from every lifeboat and the sinking Collapsible B were on board the rescue ship Carpathia before climbing the ship’s rope ladder to safety.

As the highest ranking officer to survive, Lightoller testified at the American inquiry. He staunchly defended the actions of Titanic’s crew, including that of Captain Smith. He returned to sea the following year as First Officer on the Oceanic. With the start of World War I, the Oceanic became an armed merchant cruiser and Lightoller became a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy. When it ran aground, he again supervised the filling of lifeboats. He was then given command of a torpedo boat which collided with a trawler and sank, exactly six years, nearly to the minute, after the Titanic sinking.

At war’s end, Lightoller left the Royal Navy as full Commander and returned to White Star for several years. Then during World War II, the sixty-six-year-old helped rescue 130 soldiers from the beaches at Dunkirk using his own yacht. He lost two sons in the war.

“Lights” went on to run a boatyard and build motor launches for the London River Police in his 70s. He died in 1952, at the age of 78.