What the Doctor Saw

/Dr. Washington Dodge boarded the Titanic in Southampton with his wife and five-year-old son, following a short European vacation. They were on their way home to San Francisco, where Dr. Dodge had been elected to his fourth term as city assessor following a successful career as a physician.

Dr. Washington Dodge

Following Titanic’s collision with the iceberg, Mrs. Dodge and her son were helped into Lifeboat 5. Dr. Dodge managed to find a seat in Lifeboat 13. Twelve-year-old Ruth Becker was put into the same boat, after she was separated from her family. In my novel, Ruth learns Dr. Dodge’s name as they await rescue.

Mrs. Dodge and son Washington Jr.

He is quoted in the San Francisco Bulletin later that week, after his return home.“I watched the lowering of the boat in which my wife and child were until it was safely launched…and I remained on the starboard side where the boats with the odd numbers from one to fifteen were being prepared…I waited until what I thought was the end. I certainly saw no sign of women or children on deck when I was told to take a seat in boat No. 13.”

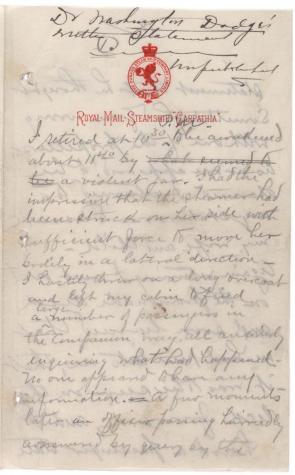

Dr. Dodge's account of the sinking, written aboard the Carpathia

He described a gushing stream of water from Titanic’s condenser that sent Boat 13 into the path of Boat 15 as it was lowered. He then told what happened after the lifeboat was finally rowed away from the ship.

“We saw the sinking of the vessel. The lights continued burning all along its starboard side until the moment of its downward plunge. After that a series of terrific explosions occurred, I suppose either from the boilers or the weakened bulkheads."

Dodge voiced his opinion of the lifeboats. "Only one of the boats had a lantern...If a sea had been running I do not see how many of the small boats would have lived. For instance, on my boat there were neither one officer or a seaman. The only men at the oars were stewards who could no more row than I could serve a dinner."

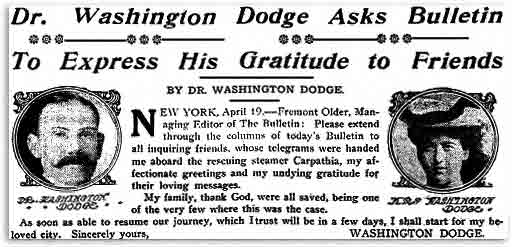

Aboard the Carpathia, Dr. Dodge was reunited with his family. Back in San Francisco, he gave interviews and spoke about his Titanic experience to several local newspapers, citing what he considered to be the many reasons why so many lives were lost. He claimed he’d seen at least one officer fire shots at male passengers from third class as they attempted to board the last boats. Other survivors gave similar stories, although they were inconsistent and none could be proven.

San Francisco Bulletin column, April 19, 1912

Seven years later, Dr. Dodge was involved in a lawsuit and was distraught over the defamation of his character, according to close friends. He shot himself at his home and died a week later at the age of 60.