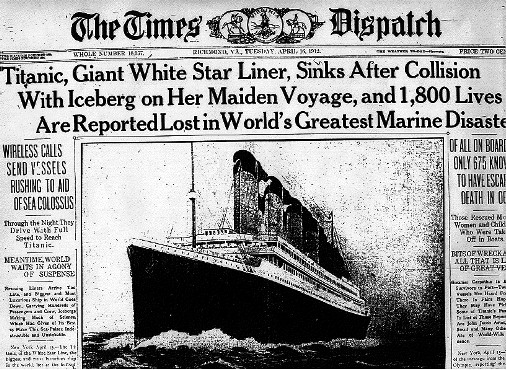

A Titanic Love Story - Part I

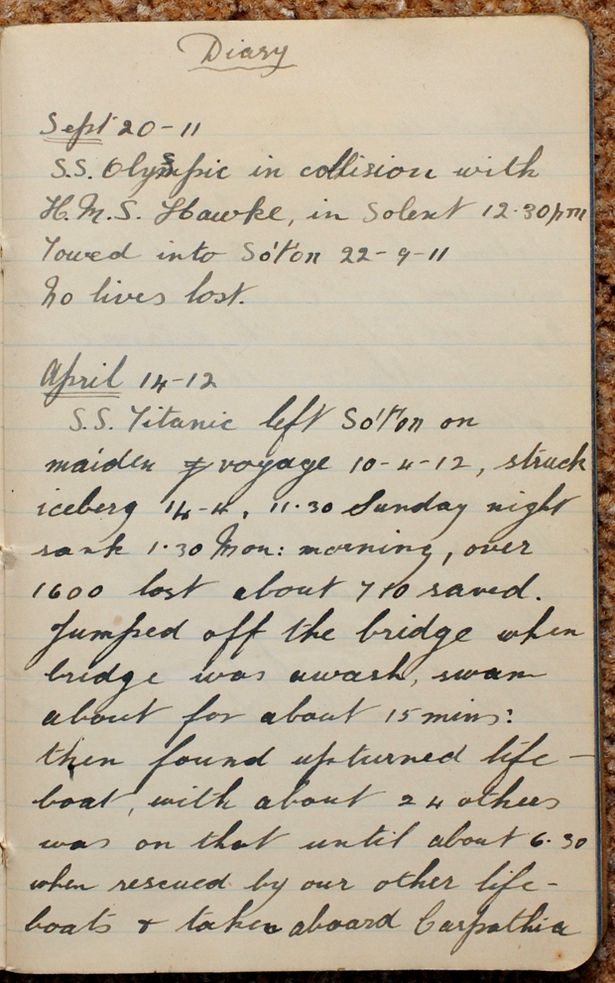

/Thirteen newlywed couples boarded Titanic—nine in first class, two in second class, and two in steerage. The youngest were teenagers, the oldest in their 40s. Some were already expecting their first child. What did they experience on that fateful night of April 14th, 1912? Did they survive? And what happened to them afterward? Beginning this week, here are their stories.

John Jacob and Madeleine Astor

Titanic's most well-known passenger, 48-year-old John Jacob Astor was one of the richest men in the world. He’d divorced his first wife, Ava, just two years before announcing his engagement to Madeleine Force. Rumors spread, especially when newspaper reporters learned Madeleine’s age. At 18, Madeleine was a year younger than the multi-millionaire’s son.

Several ministers turned down the generous fee John offered them to officiate. Finally, one agreed to perform the wedding at Astor’s Rhode Island home. Those in attendance at the romantic ceremony claimed the bride and groom were obviously in love.

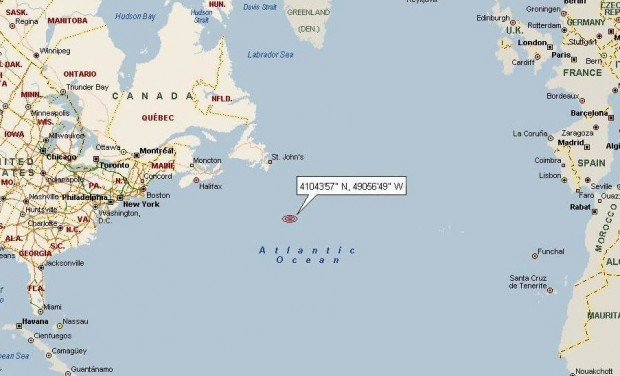

In order to quiet the scandal surrounding them, the newlyweds decided to embark on a long European honeymoon, beginning with a trans-Atlantic cruise aboard the Olympic, Titanic’s older sister. Accompanying them were John’s valet, Madeleine’s maid, and Kitty, their pet Airedale. A nurse for Madeleine, who was three months pregnant, traveled with them as well.

John Jacob Astor

Madeleine Astor

On the Olympic, the couple met Margaret Brown, an outspoken advocate for women’s suffrage. She visited the pyramids in Egypt with them, then Italy and France, where she received word that her grandson was ill back home. She booked passage on Titanic and would board at Cherbourg. Madeleine, not wanting to risk having her child far from home, asked John if they could join Margaret on the voyage.

The Astor’s were given a superior suite of rooms in Titanic’s first class section. Madeleine loved the ship but couldn’t help feel the cold stares from passengers who knew her husband and his first wife. Margaret Brown encouraged her to ignore the gossip and enjoy herself, and soon the couple became acquainted with other newlywed passengers.

When the ship struck the iceberg, John and Madeleine were sent to the boat deck and told to wear their lifebelts. Hoping another ship would come along before boarding the lifeboats became necessary, John led his wife to the gymnasium to wait. But by 1:40 am, Titanic had a severe list. Despite Madeleine’s protests, John helped her board Lifeboat 4 and asked Second Officer Lightoller if he could join her. When his request was denied, he helped Madeleine’s maid and nurse board the boat, then waved goodbye.

Madeleine hoped her husband would take another lifeboat. She helped row Lifeboat 4 until the Carpathia came to their rescue the next morning. On board, she asked everyone about her husband until it was finally determined that he had been one of the many men who had gone to their death. Madeleine was inconsolable.

John Jacob Astor’s body was recovered and a private funeral held at the family’s Rhode Island estate. His pockets contained $2,500 in cash and a watch that had stopped at 3:20.

Madeleine gave birth to a healthy baby boy exactly four months later and named him John Jacob. She remained in mourning a long time for the man she had loved, caring for her baby and only seeing close friends. A pre-nuptial agreement stated that she was entitled to interest on a five-million-dollar trust fund as long as she didn’t remarry. But in 1916, she married a childhood friend, ending her rights to the Astor money. She had two more sons, and died in 1940 in Palm Beach, Florida.