The Publisher and the Pekinese

/Beginning this week, I wish to to introduce you to some of the real Titanic passengers and crewmembers who have a role in my pre-published novel, which is based on the true story of 12-year-old passenger Ruth Becker. (Some of the real-life characters in the novel have already been featured on the blog, such as Captain Edward Smith, passenger John Jacob Astor, and orchestra leader Wallace Hartley.) We’ll start with a man Ruth meets on her first venture onto Titanic’s Promenade Deck, as he struggles to hold a very wiggly Pekinese...

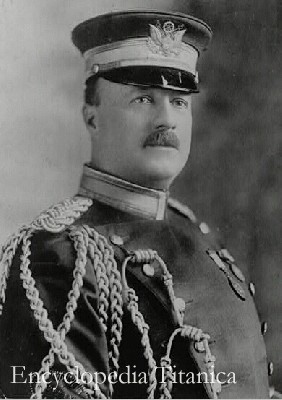

Henry Sleeper Harper was the director of Harper and Brothers Publishing House, which his grandfather had founded in the 1800s but was not formally dedicated to publishing until 1900. The firm published several magazines, including Harper’s Weekly and Harper’s Bazaar. Henry also served on the board for the protection of the Adirondacks, and was instrumental in preventing logging of the area.

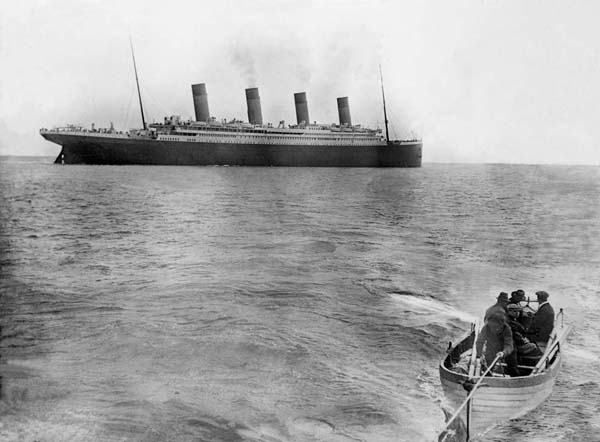

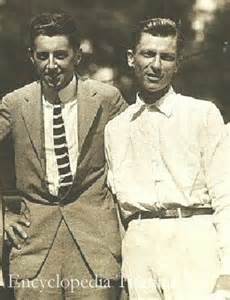

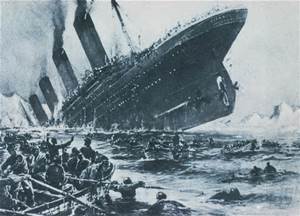

Forty-eight-year-old Henry and his wife, Myra, boarded the Titanic at Cherbourg, France, along with their Egyptian interpreter and guide, Hammad. The Harpers had been in Paris, where their Pekinese dog, Sun Yat Sen, had won a top prize at a dog show.

Sun Yat Sen

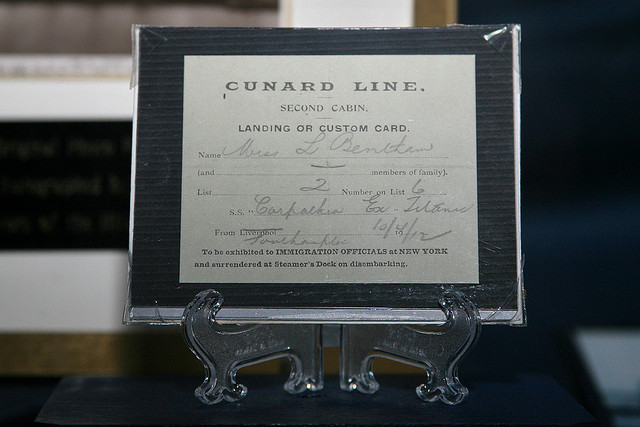

On the night of the sinking, the couple were finishing a late dinner when they were told to return to their cabin for warm clothes and lifebelts and report to the Boat Deck. They headed for the starboard side and boarded Lifeboat 3, along with Hammad and Sun Yat Sen. All were rescued by the Carpathia. Sun Yat Sen was one of three dogs that survived the sinking of the Titanic. In regard to being allowed to board the lifeboat with a dog, Harper replied later, “There seemed to be plenty of room at the time and no one offered any objection.”

Mrs. Henry Harper with Sun Yat Sen

The Harpers did not have children, and Myra died in 1923. Henry married Anne Hopson and had a son, also named Henry. Henry Sleeper Harper died at the age of 79 after a lengthy illness. He is buried in New York City, along with Myra and Anne.

In the 1990s, the company merged with William Collins & Sons of Great Britain to form HarperCollins.

photo credits: Encyclopedia Titanica