The Artist Aboard Titanic

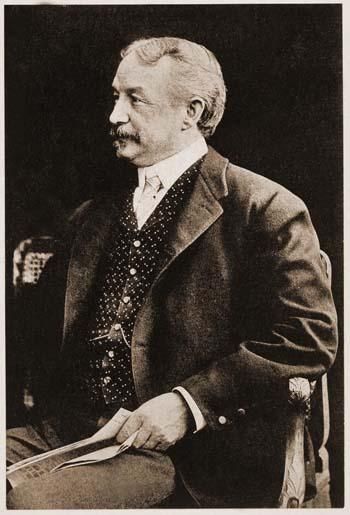

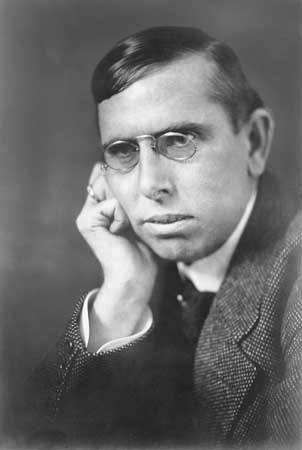

/One of Titanic's many famous passengers was Francis Davis Millet. During the Civil War, Millet had served as a drummer boy and later as a surgical assistant. He entered Harvard, became a reporter, and enjoyed drawing portraits of friends in his spare time. He then turned seriously to art and studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Belgium, winning medals for his work. Millet continued to work as a journalist and translator during the Russian-Turkish War, and later published accounts of his travels as well as short stories and essays.

f-millet

Frank Millet

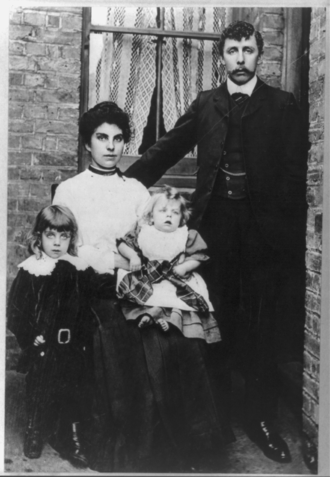

Millet married, and the couple had four children. He became an accomplished painter and organized the American Federation of the Arts for the National Academy. His paintings can be seen in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Tate Gallery in London, Trinity Church in Boston, and several other public buildings throughout the United States. His many friends included President William Howard Taft, author Mark Twain, and impressionist artist John Singer Sargent.

450px-francis_davis_millet_ca1900

Millet at work in his studio

a_cosey_corner_t

A Cozy Corner

a_difficult_duet_t

A Difficult Duet

between_two_fires_t

Between Two Fires

francis-davis-millet-playing-with-baby

Playing With Baby

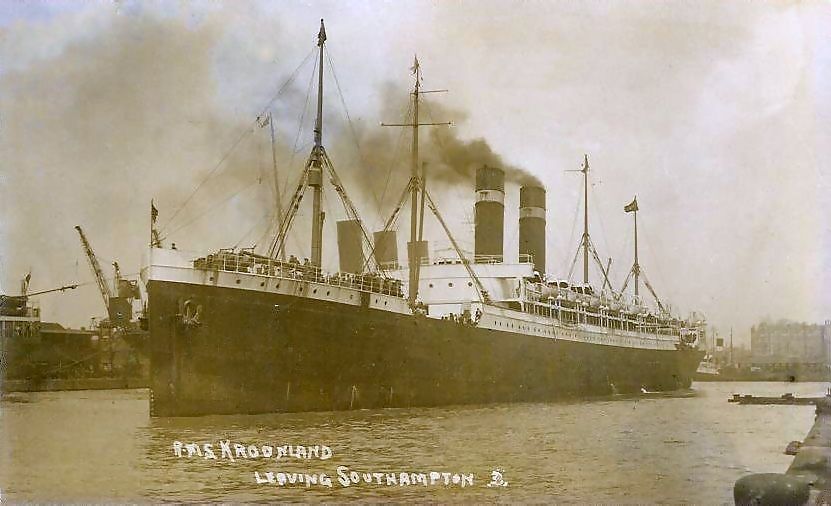

In 1912, Millet persuaded another friend, Major Archibald Butt, 45, to join him on a six-week trip to Europe. Butt, whose health had recently deteriorated, was a close friend and military aide to President Taft. They visited Naples, Gibraltar, and Rome, where Butt met with Pope Pius X. The men booked first class tickets for their return voyage to the US on the Titanic.

While the ship was docked at Queenstown, Ireland, Millet wrote to a friend with his opinion of some of his fellow passengers: "Obnoxious, ostentatious American women are the scourge of any place they infest and worse on shipboard than anywhere. Many of them carry tiny dogs and lead husbands around like pet lambs. I tell you, when she starts out, the American woman is a buster. She should be put in a harem and kept there."

Following the collision and rescue, Colonel Archibald Gracie testified he had seen Millet and Butt playing bridge with two other male passengers before the ship hit the iceberg. He stated the card game had continued with barely an interruption, even as the lifeboats were loaded. Other survivors recalled seeing Millet and Butt helping women and children into lifeboats.

Frank Millet’s body was recovered by the Mackay-Bennett and sent to Boston for burial. He was 65. The body of Archibald Butt was not recovered. A memorial fountain was dedicated to the two men in Washington D.C.

butt-millet-fountain

Butt-Millet Memorial Fountain

Photo credits: jssgallery.org, nationalarchives.gov.uk, passionforpaintings.com, Wikipedia.com